What seems a long time ago, February 2019, I presented a session as part of the Teaching and Learning Conversations series which presented a model for digital support and development we are using at the University of Liverpool.

Subsequently Chris Kennedy posted on twitter relating to this topic to which I responded (he’s usefully summarised those conversations in a blog post) and I promised I would expand on my slides with a more detailed blog post.

Full set of the original slides below:

Part one: Terminolgy

I begin with posing a question:

I started with this question because from my own experience the terminology we use can sometimes influence the engagement we get from the range of stakeholders. Also terminology is something we consistently fail to agree on as a field (hyflex/hybrid/blended as an example).

My point here is that the terminology has to feel integrative – for example it’s not good having an e-learning team if the institution has a “digital education” framework (or vice versa). These things need to join up. (By the way “technology enhanced learning” (TEL) generally comes out on top).

Proposition 1: We must get the terminology right – it needs to be integrative.

Part TWO: STRUCTURES

When I talk about structures I don’t just mean within a TEL team, but more broadly across the institution. This is closely related to terminology as both impact on a stakeholders perception of who to go to for advice and where to seek support. For a member of teaching staff wanting assistance the reality is they don’t really care where the support comes from, just that they get the support they are seeking in a timely manner. Whilst we (in educational development) might understand our role and how it differs from IT support there will always be colleagues who don’t.

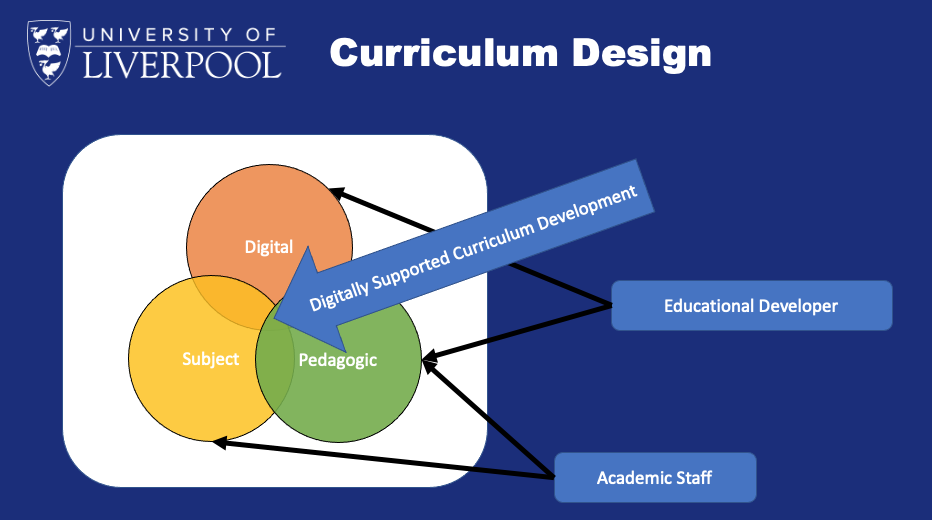

As with many institutions I have worked at, or with, the library and IT support teams have often provided front line support for staff and students in various forms relating to technical support, and I don’t see any reason to change this approach. What I want to focus on here is the way in which “digital” is embedded within a curriculum development process. The structure diagram below reflects the current model at the University of Liverpool.

The library and IT services generally operate independently (although there is of course an interdependent relationship. Perhaps more interestingly at Liverpool “Academic Development” (i.e. the professional development of the individual academic) is in a separate department (The Academy) from curriculum development which which undertaken by the Centre for Innovation in Education (CIE), although they operate with a great deal of interdependency.

It is within CIE that ‘digital education’ sits and it is within that context I will be exploring the notion of a ‘digitally support curriculum’.

Proposition 2: We need to get our structures right – it needs to support integration.

Part THREE: ROLES

It is perhaps the ‘roles’ which Chris Kennedy was more specifically alluding to in his blog post (as mentioned at the start of this post) and tweet (below).

It’s certainly hard not to argue that the role of the “learning technologist” has and will continue to change, and the four part blog series on the Association for Learning Technology is testament to that.

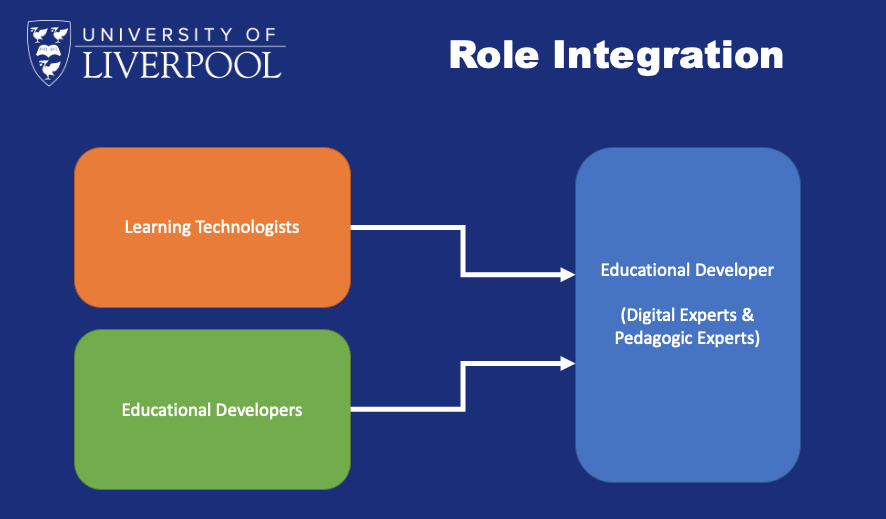

Additionally Dr Claire Gordon proposed that we will see a merging into a single role on a continuum.

It was this point at which I joined the conversation and put forward the work we have already done in the Centre of Innovation in Education to move towards this.

Historically our educational developers and learning technologists have been separately defined roles. My observation has been that this separation only upholds the notion that “digital” is a separate element to the wider curriculum development activity and as such treated as a “bolt on”.

It has always been my philosophy (both as an academic and as an educational developer) that a digitally supported curriculum is one within which the digital tools and systems are an integral to the discussions and part of the curriculum design process, never more so than now, at a time where digital spaces for learning and teaching are being more widely accepted than ever before.

Over the past two years we have phased out the role of ‘learning technologist’ and focussed on broadening the educational developer role, to encompass both digital and pedagogical expertise. Some of our educational developers expertise is more heavily weighted towards pedagogy and some toward digital, but with an appreciation and base understanding of both.

Proposition 3: We must get our roles right – everyone needs to feel integrated.

Part FOUR: process

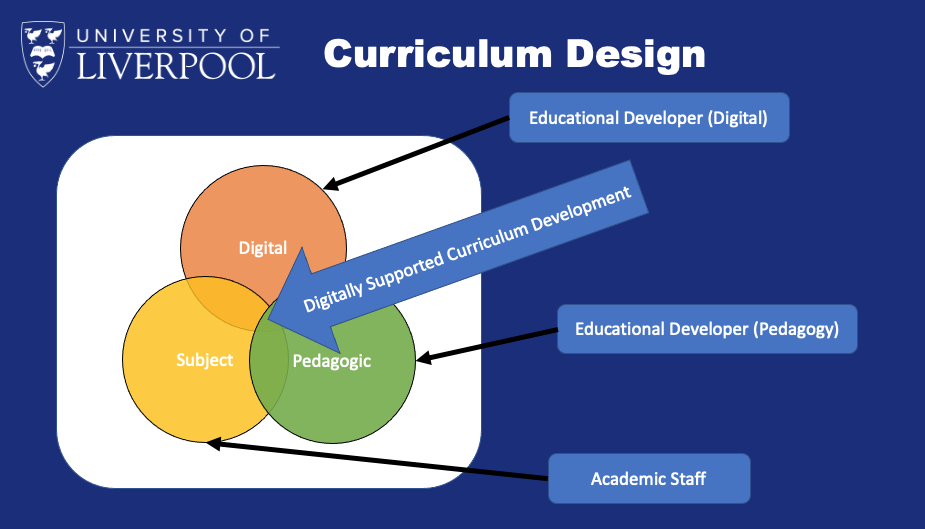

The concluding aspect to this approach is then how we connect this work to our curriculum design process. The key here is building a model of partnership, one within which a range of stakeholders work collaboratively to support and develop a module, course or programme.

The role of our educational developers is to support our academic departments to develop curriculum that draws upon the very best learning and teaching approaches (including the use of digital tools) within the context of the discipline.

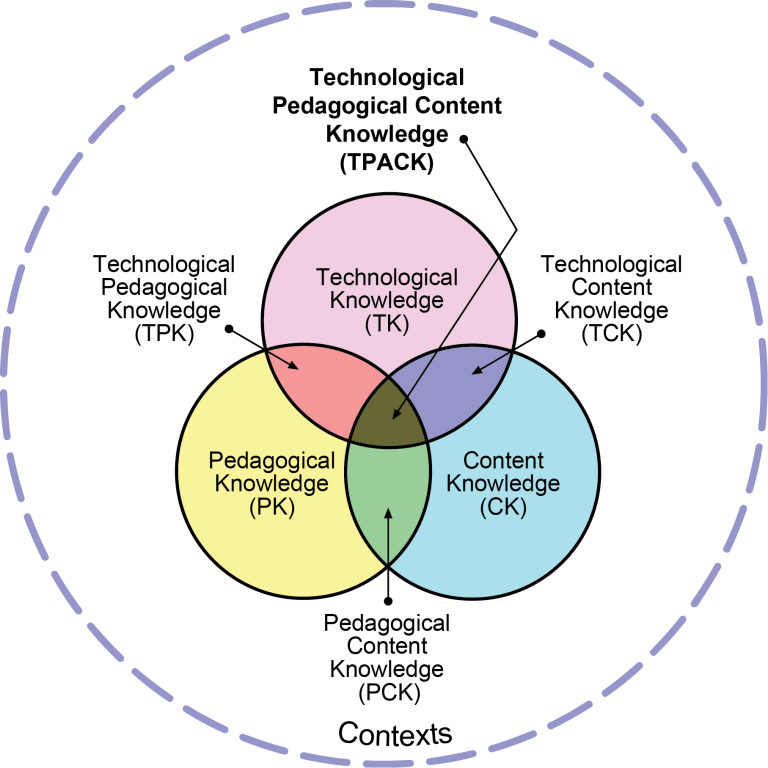

In order to frame this discussion we use TPACK (Koehler, M., & Mishra, P. 2009) which proposes three core dimensions (and more importantly an interplay of each) to support the development of the ‘teacher’.

We have used this framework in support of our own curriculum development approach, and in particular use it to explain how we seek to work in partnership to maximise the skillsets we have.

At a very simplistic level we can simply map each role to the framework, with each role bringing a specific area of expertise to the framework dimensions.

The reality of course is much more complex, with one role potentially able to bring expertise to all two or more domains and there are a whole set of contexts that need to be taken into account, but the emphasis here is always on partnership and valuing the contribution of each role.

In some cases the academic staff are able to bring expertise to all three domains, but that does not mean an educational developer should be excluded from working with them, as their perspective and experience will be different and the role of ‘critical friend’ is integral to the partnership model.

Proposition 4: We must get our process(es) right – it must encourage integration.

Digital PEDAGOGY

Whilst the main focus here has been around digital integration and the approaches we might take to achieve that I don’t want us to think that digital is the answer before we have even heard the question. It’s important that as an educational field of expertise we are critical of ourselves and our work.

As a community we have been guilty (and I include myself in this) of having a largely positivist attitude to technology in the fact it is almost always a good thing (in learning and teaching). WE only have to look at the term TEL (technology enhanced learning) as a nod to that.

However, we need to recognise that the use of digital tools and systems is much more complex than that and in some cases negatively impacts our students and teachers. So I want to end with a quote which underpins my philosophy to working within the sphere of digital education and why the partnerships and conversations are so important:

Digital Pedagogy is precisely not about using digital technologies for teaching and, rather, about approaching those tools from a critical pedagogical perspective. So, it is as much about using digital tools thoughtfully as it is about deciding when not to use digital tools, and about paying attention to the impact of digital tools on learning.

https://hybridpedagogy.org/tag/what-is-digital-pedagogy/

3 Responses